CURIOSITIES

History: Humanistic contributions to society

This Month Medical Calendar

December

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

December 1

World AIDS Day

Every year on December 1, we observe World AIDS Day to raise awareness,

honor those who have passed away, and recognize progress in HIV prevention and

treatment.

✅ What is AIDS?

AIDS is the most advanced stage of infection caused by the HIV virus.

HIV weakens the immune system. When defenses are very low, people can

develop serious infections, certain cancers, and other complications that may

become life-threatening.

✅ What is the difference between HIV and AIDS?

* HIV is the virus that attacks the immune system.

Many people with HIV never develop AIDS if they receive timely and

appropriate treatment.

* AIDS is the final and most severe stage of HIV infection, when the immune

system is badly damaged.

Thanks to modern treatments, many people with HIV live healthy, long lives.

✅ How is HIV transmitted?

HIV can be transmitted through:

* Unprotected sexual contact

* Blood exposure (e.g., sharing needles)

* From mother to baby during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding

HIV is NOT transmitted by:

* Saliva

* Hugging or casual contact

* Sharing food or utensils

✅ Prevention

Ways to reduce the risk of HIV infection include:

* Using condoms consistently and correctly

* Not sharing needles or syringes

* Getting tested regularly

* Starting treatment early if you have HIV

Early diagnosis and proper treatment help control the virus and prevent

progression to AIDS.

December 3

International Doctor’s Day

Every year on December 3, we celebrate International Doctor’s Day.

This date honors Cuban physician Carlos Finlay, who discovered that the Aedes

aegypti mosquito transmits yellow fever, and recognizes all medical professionals

who work daily to protect people’s health and save lives.

✅ The role of physicians

Doctors are dedicated professionals who prevent, diagnose, and treat diseases

to improve people’s health and quality of life.

They care for routine check-ups, emergencies, and complex medical cases, always

striving to restore health and support their patients.

✅ The Hippocratic Oath

Medical practice is guided by strong ethical values, reflected in the Hippocratic

Oath, created by Hippocrates — known as the “Father of Medicine.”

This oath symbolizes the commitment, compassion, and service that define the

medical profession.

✅ Humanitarian medical work

Thousands of doctors participate in humanitarian organizations that assist people

in vulnerable situations around the world, including:

* Doctors of the World: Provides medical support to underserved

communities in more than 14 countries.

* Doctors Without Borders (MSF): Delivers emergency medical care in

areas affected by war, epidemics, natural disasters, and lack of healthcare.

Their work saves lives and brings essential care to those who need it most.

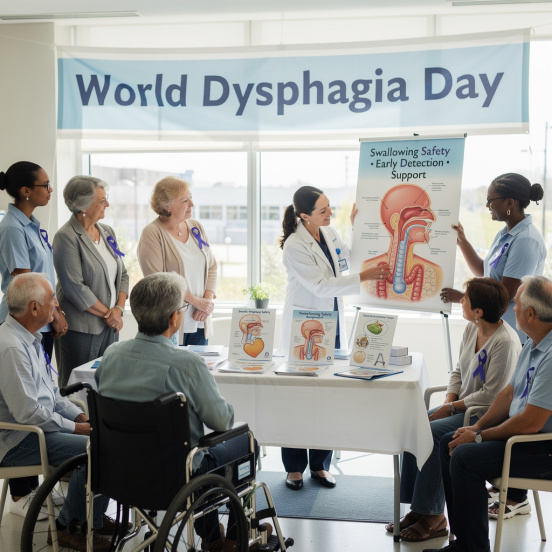

December 12

World Dysphagia Day

December 12 marks World Dysphagia Day, raising awareness about a condition

that makes it difficult to swallow food or liquids.

It requires medical attention, as it can lead to breathing problems, malnutrition, and

other serious health issues.

✅ What is dysphagia?

Dysphagia is the difficulty swallowing, caused by problems in the mouth, throat,

or esophagus.

It may cause pain when eating, a feeling that food is stuck, coughing, or weight

loss.

✅ Why does it occur?

Dysphagia can have many causes, including:

* A condition called achalasia, where the muscle at the bottom of the

esophagus does not relax properly

* Involuntary or uncoordinated movements of the esophagus

* Tumors or physical obstructions

* More common in older adults due to difficulty swallowing larger pieces of

food

✅ Main symptoms

* Pain or discomfort when swallowing

* Feeling that food is stuck

* Hoarse voice

* Regurgitation (food coming back up)

* Heartburn

* Coughing while eating

* Sudden weight loss

✅ How to improve or prevent dysphagia

Healthy habits play an essential role:

* Follow the diet recommended by your healthcare provider

* Chew food slowly

* Avoid smoking and alcohol

* Consult a nutrition specialist to maintain a balanced diet

* Seek medical advice if symptoms appear

Good eating habits may help reduce the risk, even in people without symptoms.

✅ Treatment

Treatment depends on the cause:

* Dietary changes (softer or thickened foods)

* Nutritional supplements

* Therapy with specialists

* In more serious cases (e.g., tumors or strictures), medical treatment or

surgery may be required

✅ Living with dysphagia

Dysphagia can affect daily life physically and emotionally.

Support from family, caregivers, and the community is crucial for maintaining a high

quality of life.

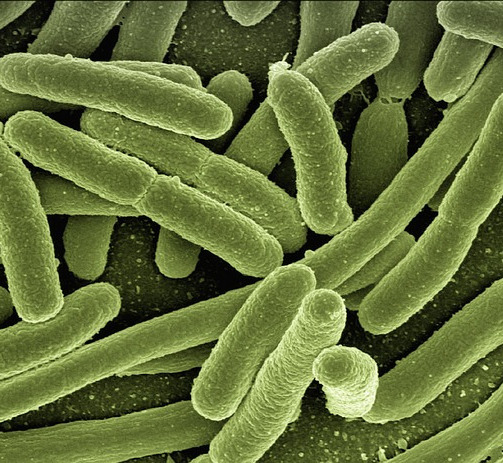

December 27

International Day of

Epidemic Preparedness

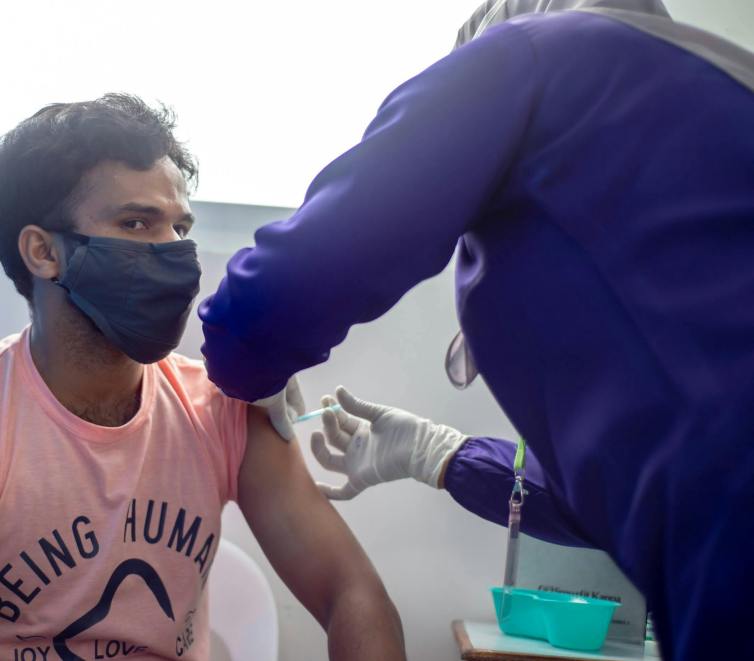

The United Nations (UN) declared December 27 as the International Day of

Epidemic Preparedness.

This day highlights the global impact of infectious diseases, epidemics, and

pandemics on health, society, and the economy — especially in vulnerable

countries.

The date also honors Louis Pasteur, pioneer of modern microbiology and

preventive medicine.

✅ Purpose of this observance

This day calls on governments, international organizations, the private sector, and

communities to:

* Promote awareness, prevention, and control of epidemics

* Strengthen health systems

* Support education and vaccination campaigns

* Improve emergency preparedness and response

Natural disasters and humanitarian crises can increase the risk of epidemics by

weakening health services and basic living conditions.

✅ Key concepts

* Outbreak: A sudden increase in cases of a disease in a specific place and

time.

Example: meningitis, measles.

* Epidemic: A sharp rise in cases of a disease in a region, above what is

usually expected.

* Pandemic: An epidemic that spreads across multiple countries or

continents with community transmission.

Example: COVID-19.

* Endemic: A disease that is consistently present in a specific area.

✅ Major epidemics in history

* Bubonic plague: (6th–14th centuries) caused millions of deaths; killed

about one-third of Europe’s population.

* Spanish flu (1918–1919): one of the deadliest pandemics; caused an

estimated 20–40 million deaths.

* Cholera: multiple global outbreaks since 1817; continues to affect several

regions.

* Avian influenza: primarily affects birds but can infect humans.

* Ebola: severe viral disease with outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa (notably

2014–2015).

* COVID-19 (2020–present): pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 with millions

of cases and deaths worldwide.

* HIV/AIDS (1981–present): infection that weakens the immune system;

more than 75 million people affected.

✅ How can epidemics be prevented and

controlled?

* Public education and awareness

* Vaccination programs

* Strengthening health systems, especially in vulnerable communities

* Improved disease surveillance

* International cooperation and coordinated response

Global collaboration — including support from the UN and the World Health

Organization (WHO) — is essential to prevent, detect, and respond to epidemics

and infectious diseases.

November

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

November 6th

Malaria Day in the Americas

Every November 6, we observe Malaria Day in the Americas, an initiative led by the Pan American Health Organization to remind us that this disease is preventable and treatable.

What is malaria?

Malaria (or paludism) is an illness caused by parasites transmitted through the bite of an infected Anopheles mosquito.

Who is most affected?

In 2019, there were an estimated 229 million cases worldwide.

Children under 5 are the most vulnerable group.

Most cases occur in Sub-Saharan Africa, as well as parts of Asia and Latin America.

Common symptoms

Symptoms usually appear a few days after the mosquito bite and may include:

• Fever

• Headache

• Vomiting

• Chills and sweating

In children, the disease can be more severe, causing anemia or breathing difficulties.

Diagnosis and treatment

Malaria is diagnosed using a blood sample or rapid diagnostic tests in remote areas.

It can be treated. Common treatments include:

• Chloroquine (for Plasmodium vivax)

• Artemisinin-based combination therapies (for Plasmodium falciparum)

How can it be prevented?

Key prevention measures include:

• Indoor spraying with insecticides

• Insecticide-treated bed nets to avoid mosquito bites

✔ Malaria is preventable and treatable. Early detection saves lives.

November 14th

World Diabetes Day

Every year on November 14, we observe World Diabetes Day, a global initiative created by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and the World Health Organization (WHO) to raise awareness about the increasing number of diabetes cases worldwide.

The date honors the birthday of Frederick Banting, who, together with Charles Best, helped discover insulin in 1921.

What is diabetes?

Diabetes occurs when the body does not produce enough insulin or cannot use it properly.

Insulin is a hormone that regulates blood sugar. If diabetes is not managed, blood sugar levels can rise too high (hyperglycemia), causing serious health problems.

Main types

• Type 1 diabetes: the pancreas does not produce insulin.

• Type 2 diabetes: the body does not use insulin effectively. This is the most common type and can often be prevented.

• Gestational diabetes: occurs during pregnancy. It increases the risk of complications for both mother and baby.

Common symptoms

Symptoms can be subtle. Talk to your doctor if you notice:

• Excessive thirst and frequent urination

• Tiredness

• Rapid weight loss

• Blurred vision, slow-healing wounds, frequent infections, or tingling in hands or feet

Treatment

Treatment may include oral medications or insulin, depending on the patient’s needs.

✔ Early detection and proper management help prevent complications.

November 17th

International Lung Cancer Awareness Day

Every year on November 17, we observe International Lung Cancer Awareness Day, highlighting a serious disease that affects both men and women worldwide.

Prevention is essential, especially by avoiding major risk factors such as smoking, exposure to toxic substances, and air pollution.

What is lung cancer?

Lung cancer occurs when cells in the lungs grow abnormally, damaging tissues and affecting breathing.

Sometimes it causes no symptoms, but common signs may include:

• Persistent cough or coughing up blood

• Shortness of breath

• Chest pain

• Hoarseness

• Loss of appetite or sudden weight loss

Risk factors

• Smoking (causes about 85% of cases)

• Exposure to radon gas

• Contact with substances such as arsenic, diesel fumes, and industrial chemicals

• Air pollution

• Secondhand smoke

Why early diagnosis matters

Lung cancer is often detected late. A timely diagnosis can save lives by allowing access to more effective and less invasive treatments.

How to prevent it

• Do not smoke and avoid smoky environments

• Reduce exposure to toxic chemicals

• Stay physically active

• Eat a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and proteins

✔ More than 85% of lung cancer cases are linked to smoking.

Avoiding tobacco smoke saves lives.

Third Wednesday of November

World COPD Day

Every year on the third Wednesday of November, we observe World COPD Day, led by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) in collaboration with healthcare professionals and patient groups.

Its goal is to raise awareness and promote better care for people living with COPD.

What is COPD?

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) refers to lung conditions that make it hard for air to flow in and out of the lungs.

It is not just cough or shortness of breath , COPD is a serious, potentially life-threatening illness that gradually worsens if not treated.

How is it diagnosed?

A simple test called spirometry is commonly used to diagnose COPD and assess lung health throughout a person's life.

What contributes to COPD?

Besides tobacco smoke, other factors can affect lung development — from before birth through young adulthood — increasing the risk of chronic lung disease later in life. These include:

• Air pollution

• Respiratory infections

Main risk factors

• Smoking

• Indoor air pollution (e.g., smoke from biomass stoves or boilers)

• Outdoor air pollution

• Exposure to dust or chemical substances

✔ COPD is preventable and treatable. Protecting lung health from early life is essential.

Octubre

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

October 1th

International Day for Older Persons

The 2025 International Day of Older Persons, celebrated under the theme “Older persons drive local and global action: our aspirations, our well-being, and our rights,” highlights the transformative role that older persons play in building resilient and equitable societies. Far from being passive beneficiaries, they are drivers of progress, contributing their knowledge and experience in areas such as health equity, economic well-being, community resilience, and the defense of human rights.

October 10th

Mental Health World Day

The overall objective of World Mental Health Day is to raise awareness of mental health issues around the world and to mobilize efforts in support of mental health.

The Day provides an opportunity for all stakeholders working on mental health issues to talk about their work, and what more needs to be done to make mental health care a reality for people worldwide.

October 12th

World Arthritis Day

Arthritis is not a single disease but a term that encompasses over 200 different conditions affecting the joints, tissues around the joints, and other connective tissues. These conditions can cause pain, stiffness, swelling, and decreased range of motion, significantly impacting the quality of life. Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) are among the most common, disabling, and costly non-communicable diseases. Of the 200 plus conditions under the umbrella of arthritis are 22 autoimmune and autoinflammatory arthritis diseases or known as AiArthritis Diseases.

October 19th

Breast Cancer World Day

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women worldwide. In 2022, approximately 2.3 million women were diagnosed and another 670,000 died from the disease. These are not just numbers but mothers, sisters, daughters and friends that deserve hope and dignity. While the 5-year survival rates in high-income countries exceeds 90%, the figures drop to 66% in India and 40% in South Africa. These disparities are driven by unequal access to early detection, timely diagnosis and effective treatment. If the current trend continues, the incidence and mortality are projected to rise by 40% by 2050 hence the need for urgent and coordinated action. Indeed, where a woman lives should not determine whether she survives.

October 20th

World Osteoporosis Day

World Osteoporosis Day is observed annually on 20 October, and launches a year-long campaign dedicated to raising global awareness of bone health, and of the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis and metabolic bone disease. Organized by the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF), the World Osteoporosis Day campaign is accompanied by community events and local campaigns by national osteoporosis patient societies from around the world with activities in over 90 countries.

October 24th

World Polio Day

World Polio Day highlights the global efforts to end poliomyelitis (polio) worldwide. Polio is a life-threatening disease caused by the poliovirus, which the World Health Assembly committed to eradicate in 1988. The WHO European Region was declared polio-free in 2002 and has sustained this status every year since then.

Every year on 24 October, we observe World Polio Day to raise awareness of the importance of polio vaccination to protect every child from this devastating disease, and to celebrate the many parents, professionals and volunteers whose contributions make polio eradication achievable.

To ensure a polio-free future for everyone, efforts must continue to maintain high immunization coverage, implement high-quality surveillance to detect any presence of the virus, and prepare to respond in the event of an outbreak.

October 29th

Psoriasis World Day

World Psoriasis Day was proclaimed by the IFPA in 2004. This day was conceived by patients and for patients with the aim of giving a voice to more than 125 million people worldwide who suffer from psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis. The purpose of the proclamation is to increase the visibility and understanding of these diseases, combat the associated stigma and discrimination, and promote education and information about the treatment and proper care of these conditions.

September

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

September 13th

Sepsis World Day

September 13 marks World Sepsis Day, a date created to raise awareness about the importance of understanding this disease, which is very common but relatively unknown. The main objective of this event is to reduce the number of people who die from or are affected by sepsis.

Currently, sepsis kills 11 million people each year, many of them children under the age of 5, especially in poor countries.

September 15th

World Lymphoma Awareness Day

World Lymphoma Awareness Day (WLAD) is held on September 15 every year and is a day dedicated to raising awareness of lymphoma, an increasingly common form of cancer. It is a global initiative hosted by the Lymphoma Coalition (LC), a non-profit network organisation of 83 lymphoma patient groups from 52 countries around the world. WLAD was initiated in 2004 to raise public awareness of both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in terms of symptom recognition, early diagnosis and treatment.

September 16th

International Day for Interventional Cardiology

September 16 marks International Interventional Cardiology Day, a date proclaimed by the UN with the aim of improving people's health and increasing life expectancy worldwide.

The proposal was originally put forward by Argentina and seeks to raise awareness about cardiovascular diseases, available treatments, possible complications, and the importance of prevention and care, especially through education and the media.

September 21th

World Alzheimer's Day

September 21 marks World Alzheimer's Day, proclaimed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and sponsored by Alzheimer's Disease International (ADI).

Alzheimer's disease is considered the new epidemic of the 21st century.

It is estimated that by 2050, the number of people with Alzheimer's will rise to 131.5 million.

September 25th

World Pharmacists Day

September 25 marks World Pharmacists Day, established by the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP).

This took place during a Council meeting held in September 2009 in Istanbul, Turkey. The date of September 25 was chosen to commemorate the day on which the organization was created.

September 28th

World Rabies Day

September 28 marks World Rabies Day. This particular date was chosen because it was on September 28, 1895, that Louis Pasteur, the scientist and physician responsible for creating the rabies vaccine, died. This vaccine is one of the main tools used to prevent the spread of this terrible disease.

It is currently estimated that in 99% of human rabies cases, the main cause of the disease has been an infected dog that transmitted it. For this reason, the WHO, the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the Global Alliance for Rabies Control (GARC) have set themselves the goal, as part of the 2030 Agenda, of completely eradicating this disease in dogs and preventing infection and deaths in humans.

September 29th

World Heart Day

World Heart Day is celebrated on September 29, and has been since 2000, when the World Heart Federation, with the support of the World Health Organization (WHO), designated this day with the aim of raising awareness about cardiovascular diseases, their prevention, control, and treatment.

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide. Heart attacks and strokes claim more than 17 million lives each year. And it is estimated that this figure will rise to 23 million by 2030.

A large proportion of these deaths could be prevented by eating a healthy diet that reduces salt intake, exercising regularly, and avoiding tobacco use.

August

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

August 1st

World Lung Cancer Day

World Lung Cancer Day is observed annually on August 1st. It's a global initiative dedicated to raising awareness about lung cancer, its impact, and the importance of prevention, early detection, and treatment. The day also focuses on supporting those affected by the disease and emphasizing the need for collective action in the fight against lung cancer.

August 8th

Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Day

Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) Day is observed annually on August 8th. It's a day dedicated to raising awareness about the severe forms of ME/CFS and remembering those who have died from it.

The day also aims to honor individuals with severe ME/CFS and advocate for better understanding, treatment, and research.

August 21th

World DYRK 1A Syndrome Day

DYRK 1A syndrome is classified as ultra-rare, and various patient associations and groups of physicians and geneticists have promoted the celebration of its world day. Therefore, August 21 is celebrated as World DYRK 1A Syndrome Day.

This syndrome represents a set of symptoms related to a point mutation of the DYRK 1A gene. It is characterized by intellectual disability including impaired speech development, autism spectrum disorder including anxious and/or stereotypic behavioral problems and microcephaly, as well as feeding disorders, characteristic facial features, psychomotor retardation, epilepsy and other severe symptoms.

August 28th

World Turner Syndrome Day

World Turner Syndrome Day is observed annually on August 28th. The day is dedicated to raising awareness and promoting understanding of Turner syndrome, a genetic condition that affects females.

Turner syndrome occurs when one of the X chromosomes is missing or partially missing in a female. This can lead to various health and developmental challenges. World Turner Syndrome Day serves as an opportunity to educate the public about the condition, encourage research, and advocate for timely diagnosis and appropriate care for those affected.

July

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

July 8th

Allergies Awareness Day

World Allergy Day is observed on July 8th each year.

It's a joint initiative by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Allergy Organization (WAO) to raise awareness about the importance of managing and preventing allergies.

The day aims to educate people about allergies and the impact they can have on individuals and communities.

July 22nd

Brain World Day

World Brain Day is celebrated annually on July 22nd.

It's a global initiative led by the World Federation of Neurology (WFN) to raise awareness about brain health and neurological disorders.

Each year, a specific theme is chosen to highlight different aspects of brain health and encourage action.

July 27th

World Head & Neck Cancer Day

World Head and Neck Cancer Day is observed on July 27th each year.

It's a day dedicated to raising awareness about head and neck cancers, which encompass a range of cancers developing in the head and neck region, including those of the mouth, throat, voice box, and nasal passages.

July 28th

Hepatitis Awareness World Day

World Hepatitis Day is observed annually on July 28th to raise awareness about viral hepatitis, a serious liver infection.

It's one of the World Health Organization's (WHO) twelve global public health days.

The day aims to encourage action, engagement, and highlight the need for a greater global response to combat hepatitis.

June

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

June 13th

International Albinism Awareness Day

Albinism is a genetic condition inherited from both parents that occurs worldwide, regardless of ethnicity or gender.

The common lack of melanin pigment in the hair, skin and eyes of people with albinism causes vulnerability to sun exposure, which can lead to skin cancer and severe visual impairment.

As many as 1 in 5,000 people in Sub-Saharan Africa and 1 in 20,000 people in Europe and North America have albinism.

In some countries people with albinism suffer discrimination, poverty, stigma, violence and even killings.

June 14th

World Blood Donor Day

Every year countries around the world celebrate World Blood Donor Day (WBDD). The event serves to raise awareness of the need for safe blood and blood products and to thank voluntary, unpaid blood donors for their life-saving gifts of blood.

A blood service that gives patients access to safe blood and blood products in sufficient quantity is a key component of an effective health system. The global theme of World Blood Donor Day changes each year in recognition of the selfless individuals who donate their blood for people unknown to them.

June 21th

International Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Day (ALS)

Each year on June 21, the International Alliance of ALS/MND Associations recognizes Global Day – a day to raise awareness of ALS/MND, a disease that affects people in every country around the world. ALS/MND does not discriminate by race, ethnicity, income, or geography. For every person diagnosed, the impact is deeply felt by families, friends, and entire communities.

On Global Day, the ALS/MND community comes together through awareness activities that symbolize hope for a future with better treatments, a cure, and ultimately, an end to ALS/MND. Alliance members around the world use the hashtag #ALSMNDWithoutBorders to share their stories and show their support.

May

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

May 8th

World Ovarian Cancer Day

World Ovarian Cancer Day is a global observance dedicated to raising awareness about ovarian cancer, promoting early detection, and supporting those affected by the disease. This day brings together organizations, advocates, survivors, and the general public to increase knowledge about ovarian cancer, its symptoms, and the importance of research for better treatments and outcomes

May 10th

World Lupus Day

World Lupus Day serves to call attention to the impact that lupus has on people around the world. The annual observance focuses on the need for improved patient healthcare services, increased research into the causes of and cure for lupus, earlier diagnosis and treatment of lupus, and better epidemiological data on lupus globally. World Lupus Day serves to rally lupus organizations and people affected by the disease around the world for a common purpose of bringing greater attention and resources to efforts to end the suffering caused by this disabling and potentially fatal autoimmune disease.

May 12th

International Nurses Day

International Nursing Day is celebrated around the world every May 12th, the anniversary of the birth of Florence Nightingale, considered the pioneer of modern nursing. Nurses play a crucial role in healthcare systems but often lack recognition and adequate investment in education, jobs, and leadership. International Nurses Day activities aim to promote dialogue and action in gender equality, leadership, and innovation in nursing education and practice.

May 17th

World Hypertension Day

World Hypertension Day is observed every May 17th in order to raise awareness and promote hypertension prevention, detection and control (deferred to October 17, 2020, due to COVID-19 pandemic). High blood pressure is the main risk factor to develop cardiovascular disease.

More than one billion people around the world live with hypertension (high blood pressure), which is a major cause of cardiovascular disease and premature death worldwide. The burden of hypertension is felt disproportionately in low- and middle-income countries, where two thirds of cases are found, largely due to increased risk factors in those populations in recent decades. What’s more, around half of people living with hypertension are unaware of their condition, putting them at risk of avoidable medical complications and death.

To achieve the global target to reduce the prevalence of hypertension by 25% by 2025, WHO and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched the Global Hearts Initiative in 2016. With its five technical packages – HEARTS (manage cardiovascular diseases), MPOWER (control tobacco), Active (increase physical activity), SHAKE (reduce salt consumption) and REPLACE (eliminate trans fat) – the Initiative aims to improve heart health worldwide. The HEARTS technical package itself gives guidance on more effectively detecting and treating people with hypertension in primary health care.

May 25th

World Thyroid Day

May 25th was chosen in 2008 as the World Thyroid Day dedicated to thyroid patients and to all who are committed to the study and treatment of thyroid diseases worldwide. From LATS, we encourage you to spread what this day means not only among thyroid specialists but also public health policy makers. In 2011, it was the first time that World Thyroid Day was celebrated together by the four Thyroid sister Societies around the world: European Thyroid Association (ETA), American Thyroid Association (ATA), Latin America Thyroid Society (LATS) and the Asia Oceania Thyroid Association (AOTA).

April

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

March

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

March 4th

Obesity World Day

Overweight and obesity is responsible for over 90 million adult person years lost to the four leading NCDs each year. Most of these avoidable deaths and diseases are occurring in middle-income countries.

Overweight and obesity (measured by high body mass index, or BMI) are risk factors for major NCDs such as cancers, ischaemic heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. High BMI is also a risk factor for developing other NCDs including liver disease, kidney disease, musculoskeletal disorders (osteoarthritis and chronic back pain), and contributes to neurological disorders (dementia, Alzheimer’s) and poor mental health, including depression. This World Obesity Day we are critically examining the systems underlying obesity and NCDs and calling for systemic change to create healthier lives for all.

March 12th

Kidney World Day

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is estimated to affect approximately 850 million people worldwide. If left undetected and not treated timely, CKD can progress to kidney failure, leading to severe complications and premature mortality. By 2040, CKD is projected to become the 5th leading cause of years of life lost, highlighting the urgent need for global strategies to combat kidney disease.

February

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

February 4th

World Cancer Day

February 4th marks World Cancer Day, a time to reflect on the global burden of cancer, as well as to celebrate advancements in screening that have resulted in decreased mortality from the second leading cause of death worldwide.

Nearly 20 million new cancer cases are diagnosed annually, with about 9.7 million deaths according to the most recent statistics published through the World Health Organization. This means that about one in five individuals will develop cancer at some point in their lifetime.

February 14th

Congenital Heart Defect Awareness Day

February 14th is designated Congenital Heart Defect Awareness Day. This is an annual campaign to remember and honor anyone born with a heart defect. This campaign also honors all of the families and friends touched by children with heart defects along with the medical professionals caring for and conducting research to treat and prevent children born with heart defects.

February 15th

International Childhood

Cancer Day

Every day, more than 1000 children are diagnosed with cancer. This news sets all concerned on a demanding and life-changing journey. For children in high-income countries, more than 80% survive. This has been a great achievement in science, innovation and public health.

But, for many children living in low- or middle-income countries, the reality is death and immense family strain. The impact translates to lost potential, greater inequalities and economic hardship. This can and must change.

The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer aims to improve outcomes for children with cancer around the world.

February 28th

Rare Disease Day

One out of every 10 Americans is living with a rare disease. Worldwide, there are more than 300 million people with rare diseases. Too often, these individuals and families are left isolated and without answers to their medical questions. It doesn't have to be that way.

Rare Disease Day is a global initiative to raise awareness and generate support for everyone who is on a rare medical journey. It takes place on the last day of February, which this year is February 28th.

January

2025

Relevant Healthcare Dates

January 13th

World International Awareness Depression Day

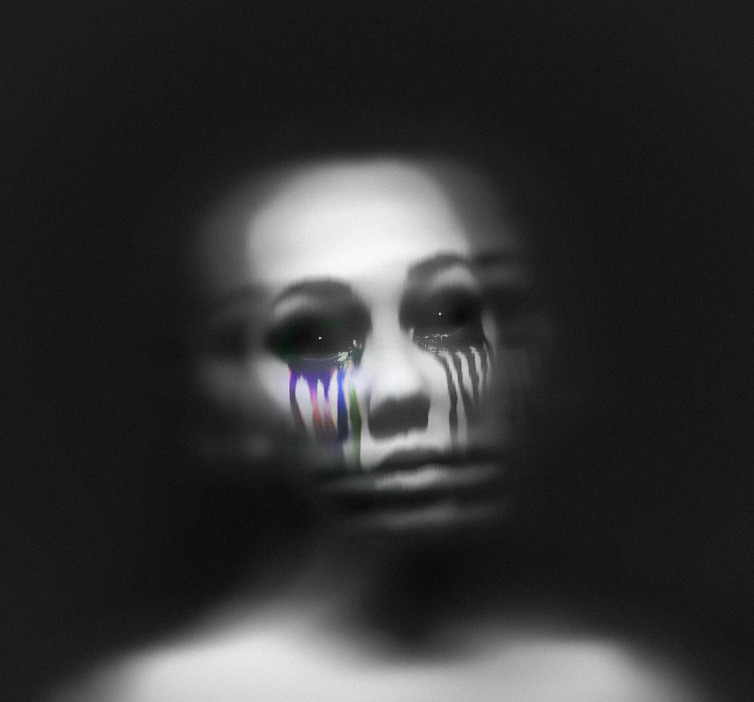

January 13th marks International Day Against Depression, an important occasion to raise global awareness about the prevalence and impact of depression, with particular focus on vulnerable populations, such as adolescents and young adults. Depression remains a pervasive public health challenge, often yielding profound emotional, psychological, and social repercussions if left unaddressed. The significance of awareness on this day cannot be overstated, as it presents an invaluable opportunity to enhance understanding of the disorder, advocate for early intervention, and foster a compassionate, interdisciplinary approach to mental health care.

January 30th

World Neglected Tropical

Diseases Day

NTDs are a group of conditions that affect more than a billion people who mostly live in marginalized, rural and poor urban areas and conflict zones. Although they are preventable and treatable, these diseases – and their intricate interrelationships with poverty and ecological systems – continue to cause devastating health, social and economic consequences.

January 26th - Last Sunday

World Leprosy Day

World Leprosy Day is observed internationally every year on the last Sunday of January to increase the public awareness of leprosy or Hansen's Disease. This date was chosen by French humanitarian Raoul Follereau as a tribute to the life of Mahatma Gandhi who had compassion for people afflicted with leprosy. The day began to be observed in 1954.

Leprosy is one of the oldest recorded diseases in the world. It is an infectious chronic disease that targets the nervous system, especially the nerves in the cooler parts of the body: the hands, feet, and face. Pope Francis has spoken in support of the observation.

DEPRESSION: History

What was previously known as melancholia and is now known as clinical depression, major depression, or simply depression and commonly referred to as major depressive disorder by many health care professionals, has a long history, with similar conditions being described at least as far back as classical times.

Ancient to medieval period

In ancient Greece, disease was thought due to an imbalance in the four basic bodily fluids, or humors. Personality types were similarly thought to be determined by the dominant humor in a particular person. Derived from the Ancient Greek melas, "black", and kholé, "bile", melancholia was described as a distinct disease with particular mental and physical symptoms by Hippocrates in his Aphorisms, where he characterized all "fears and despondencies, if they last a long time" as being symptomatic of the ailment.

Aretaeus of Cappadocia later noted that sufferers were "dull or stern; dejected or unreasonably torpid, without any manifest cause". The humoral theory fell out of favor but was revived in Rome by Galen. Melancholia was a far broader concept than today's depression; prominence was given to a clustering of the symptoms of sadness, dejection, and despondency, and often fear, anger, delusions and obsessions were included.

Physicians in the Persian and then the Muslim world developed ideas about melancholia during the Islamic Golden Age. Ishaq ibn Imran (d. 908) combined the concepts of melancholia and phrenitis. The 11th century Persian physician Avicenna described melancholia as a depressive type of mood disorder in which the person may become suspicious and develop certain types of phobias.

His work, The Canon of Medicine, became the standard of medical thinking in Europe alongside those of Hippocrates and Galen. Moral and spiritual observations also abounded, and in the Christian environment of medieval Europe, a malaise called acedia (sloth or absence of caring) was identified, involving a tendency of the will to low spirits and lethargy typically linked to isolation.

The seminal scholarly work of the 17th century was English scholar Robert Burton's book, The Anatomy of Melancholy, drawing on numerous theories and the author's own experiences. Burton suggested that melancholy could be combatted with a healthy diet, sufficient sleep, music, and "meaningful work", along with talking about the problem with a friend.

During the 18th century, the humoral theory of melancholia was increasingly being challenged by mechanical and electrical explanations; references to dark and gloomy states gave way to ideas of slowed circulation and depleted energy. German physician Johann Christian Heinroth, however, argued melancholia was a disturbance of the soul due to moral conflict within the patient.

Eventually, various authors proposed up to 30 different sub-types of melancholia, and alternative terms were suggested and discarded. Hypochondria came to be seen as a separate disorder. Melancholia and melancholy had been used interchangeably until the 19th century, but the former came to refer to a pathological condition and the latter to a temperament.

The term depression was derived from the Latin verb deprimere, "to press down". From the 14th century, "to depress" meant to subjugate or to bring down in spirits. It was used in 1665 in English author Richard Baker's Chronicle to refer to someone having "a great depression of spirit", and by English author Samuel Johnson in a similar sense in 1753. The term also came into use in physiology and economics.

An early usage referring to a psychiatric symptom was by French psychiatrist Louis Delasiauve in 1856, and by the 1860s it was appearing in medical dictionaries to refer to a physiological and metaphorical lowering of emotional function. Since Aristotle, melancholia had been associated with men of learning and intellectual brilliance, a hazard of contemplation and creativity. The newer concept abandoned these associations and, through the 19th century, became more associated with women.

Although melancholia remained the dominant diagnostic term, depression gained increasing currency in medical treatises and was a synonym by the end of the century; German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin may have been the first to use it as the overarching term, referring to different kinds of melancholia as depressive states. English psychiatrist Henry Maudsley proposed an overarching category of affective disorder.

20th and 21st centuries

In the 20th century, the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin was the first to distinguish manic depression. The influential system put forward by Kraepelin unified nearly all types of mood disorder into manic–depressive insanity. Kraepelin worked from an assumption of underlying brain pathology, but also promoted a distinction between endogenous (internally caused) and exogenous (externally caused) types.

The unitarian view became more popular in the United Kingdom, while the binary view held sway in the US, influenced by the work of Swiss psychiatrist Adolf Meyer and before him Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis.

Freud had likened the state of melancholia to mourning in his 1917 paper Mourning and Melancholia. He theorized that objective loss, such as the loss of a valued relationship through death or a romantic breakup, results in subjective loss as well; the depressed individual has identified with the object of affection through an unconscious, narcissistic process called the libidinal cathexis of the ego.

Such loss results in severe melancholic symptoms more profound than mourning; not only is the outside world viewed negatively, but the ego itself is compromised. The patient's decline of self-perception is revealed in his belief of his own blame, inferiority, and unworthiness. He also emphasized early life experiences as a predisposing factor.

Meyer put forward a mixed social and biological framework emphasizing reactions in the context of an individual's life, and argued that the term depression should be used instead of melancholia.

The DSM-I (1952) contained depressive reaction and the DSM-II (1968) depressive neurosis, defined as an excessive reaction to internal conflict or an identifiable event, and also included a depressive type of manic-depressive psychosis within Major affective disorders.

In the mid-20th century, other psycho-dynamic theories were proposed. Existential and humanistic theories represented a forceful affirmation of individualism. Austrian existential psychiatrist Viktor Frankl connected depression to feelings of futility and meaninglessness. Frankl's logotherapy addressed the filling of an "existential vacuum" associated with such feelings, and may be particularly useful for depressed adolescents.

American existential psychologist Rollo May hypothesized that "depression is the inability to construct a future". In general, May wrote that depression "occur[s] more in the dimension of time than in space," and the depressed individual fails to look ahead in time properly. Thus the "focusing upon some point in time outside the depression ... gives the patient a perspective, a view on high so to speak; and this may well break the chains of the ... depression."

Humanistic psychologists argued that depression resulted from an incongruity between society and the individual's innate drive to self-actualize, or to realize one's full potential. American humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow theorized that depression is especially likely to arise when the world precludes a sense of "richness" or "totality" for the self-actualizer.

Cognitive psychologists offered theories on depression in the mid-twentieth century. Starting in the 1950s, Albert Ellis argued that depression stemmed from irrational "should" and "musts" leading to inappropriate self-blame, self-pity, or other-pity in times of adversity. Starting in the 1960s, Aaron Beck developed the theory that depression results from a "cognitive triad" of negative thinking patterns, or "schemas," about oneself, one's future, and the world.

In the mid-20th century, researchers theorized that depression was caused by a chemical imbalance in neurotransmitters in the brain, a theory based on observations made in the 1950s of the effects of reserpine and isoniazid in altering monoamine neurotransmitter levels and affecting depressive symptoms. During the 1960s and 70s, manic-depression came to refer to just one type of mood disorder (now most commonly known as bipolar disorder) which was distinguished from (unipolar) depression. The terms unipolar and bipolar had been coined by German psychiatrist Karl Kleist.

The term major depressive disorder was introduced by a group of US clinicians in the mid-1970s as part of proposals for diagnostic criteria based on patterns of symptoms (called the Research Diagnostic Criteria, building on earlier Feighner Criteria), and was incorporated into the DSM-III in 1980. To maintain consistency the ICD-10 used the same criteria, with only minor alterations, but using the DSM diagnostic threshold to mark a mild depressive episode, adding higher threshold categories for moderate and severe episodes.

DSM-IV-TR excluded cases where the symptoms are a result of bereavement, although it was possible for normal bereavement to evolve into a depressive episode if the mood persisted and the characteristic features of a major depressive episode developed. The criteria were criticized because they do not take into account any other aspects of the personal and social context in which depression can occur. In addition, some studies found little empirical support for the DSM-IV cut-off criteria, indicating they are a diagnostic convention imposed on a continuum of depressive symptoms of varying severity and duration.

The ancient idea of melancholia still survives in the notion of a melancholic sub-type. The new definitions of depression were widely accepted, albeit with some conflicting findings and views, and the nomenclature continues in DSM-IV-TR, published in 2000.

There has been some criticism of the expansion of coverage of the diagnosis, related to the development and promotion of antidepressants and the biological model since the late 1950s.

SOURCE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_depression

PANDEMICS IN HISTORY

Historical accounts of epidemics are often vague or contradictory in describing how victims were affected. A rash accompanied by a fever might be smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, or varicella, and it is possible that epidemics overlapped, with multiple infections striking the same population at once. It is often impossible to know the exact causes of mortality, although ancient DNA studies can sometimes detect residues of certain pathogens.

It is assumed that, prior to the Neolithic Revolution around 10,000 BC, disease outbreaks were limited to a single family or clan, and did not spread widely before dying out. The domestication of animals increased human-animal contact, increasing the possibility of zoonotic infections. The advent of agriculture, and trade between settled groups, made it possible for pathogens to spread widely. As population increased, contact between groups became more frequent. A history of epidemics maintained by the Chinese Empire from 243 B.C. to 1911 A.C. shows an approximate correlation between the frequency of epidemics and the growth of the population.

The incomplete list of known epidemics which spread widely enough to merit the title "pandemic".

Plague of Athens (430 to 426 BC): During the Peloponnesian War, an epidemic killed a quarter of the Athenian troops and a quarter of the population. This disease fatally weakened the dominance of Athens, but the sheer virulence of the disease prevented its wider spread. The exact cause of the plague was unknown for many years. In January 2006, researchers from the University of Athens analyzed teeth recovered from a mass grave underneath the city and confirmed the presence of bacteria responsible for typhoid fever.

Antonine Plague (165 to 180 AD): Possibly measles or smallpox brought to the Italian peninsula by soldiers returning from the Near East, it killed a quarter of those infected, up to five million in total.

Plague of Cyprian (251–266 AD): A second outbreak of what may have been the same disease as the Antonine Plague killed (it was said) 5,000 people a day in Rome.

Plague of Justinian (541 to 549 AD): Also known as the First Plague Pandemic. This epidemic started in Egypt and reached Constantinople the following spring, killing (according to the Byzantine chronicler Procopius) 10,000 a day at its height, and perhaps 40% of the city's inhabitants. The plague went on to eliminate a quarter to half the human population of the known world and was identified in 2013 as being caused by bubonic plague.

Black Death (1331 to 1353): Also known as the Second Plague Pandemic. The total number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 75 to 200 million. Starting in Asia, the disease reached the Mediterranean and western Europe in 1348 (possibly from Italian merchants fleeing fighting in Crimea) and killed an estimated 20 to 30 million Europeans in six years; a third of the total population, and up to a half in the worst-affected urban areas. It was the first of a cycle of European plague epidemics that continued until the 18th century; there were more than 100 plague epidemics in Europe during this period, including the Great Plague of London of 1665–66 which killed approximately 100,000 people, 20% of London's population.

1817–1824 cholera pandemic. Previously endemic in the Indian subcontinent, the pandemic began in Bengal, then spread across India by 1820. The deaths of 10,000 British troops were documented - it is assumed that tens of thousands of Indians must have died. The disease spread as far as China, Indonesia (where more than 100,000 people succumbed on the island of Java alone) and the Caspian Sea before receding. Subsequent cholera pandemics during the 19th century are estimated to have caused many millions of deaths globally.

Great Plague of Marseille in 1720 killed a total of 100,000 people

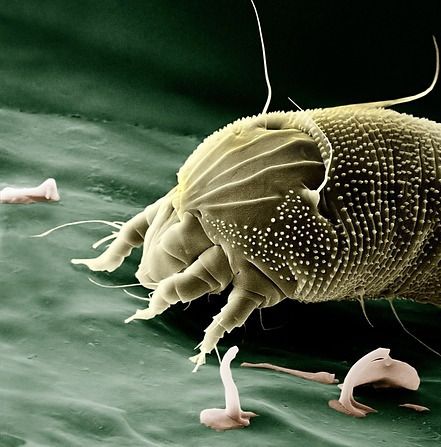

Third plague pandemic (1855–1960): Starting in China, it is estimated to have caused over 12 million deaths in total, the majority of them in India. During this pandemic, the United States saw its first outbreak: the San Francisco plague of 1900–1904. The causative bacterium, Yersinia pestis, was identified in 1894. The association with fleas, and in particular rat fleas in urban environments, led to effective control measures. The pandemic was considered to be over in 1959 when annual deaths due to plague dropped below 200. The disease is nevertheless present in the rat population worldwide and isolated human cases still occur.

The 1918–1920 Spanish flu infected half a billion people around the world, including on remote Pacific islands and in the Arctic—killing 20 to 100 million. Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill the very young and the very old, but the 1918 pandemic had an unusually high mortality rate for young adults. Mass troop movements and close quarters during World War I caused it to spread and mutate faster, and the susceptibility of soldiers to the flu may have been increased by stress, malnourishment and chemical attacks. Improved transportation systems made it easier for soldiers, sailors and civilian travelers to spread the disease.

Pandemics in indigenous populations

Beginning from the Middle Ages, encounters between European settlers and native populations in the rest of the world often introduced epidemics of extraordinary virulence. Settlers introduced novel diseases which were endemic in Europe, such as smallpox, measles, pertussis and influenza, to which the indigenous peoples had no immunity. The Europeans infected with such diseases typically carried them in a dormant state, were actively infected but asymptomatic, or had only mild symptoms.

Smallpox was the most destructive disease that was brought by Europeans to the Native Americans, both in terms of morbidity and mortality. The first well-documented smallpox epidemic in the Americas began in Hispaniola in late 1518 and soon spread to Mexico. Estimates of mortality range from one-quarter to one-half of the population of central Mexico. It is estimated that over the 100 years after European arrival in 1492, the indigenous population of the Americas dropped from 60 million to only 6 million, due to a combination of disease, war, and famine. The majority these deaths are attributed to successive waves of introduced diseases such as smallpox, measles, and typhoid fever.

In Australia, smallpox was introduced by European settlers in 1789 devastating the Australian Aboriginal population, killing an estimated 50% of those infected with the disease during the first decades of colonization. In the early 1800s, measles, smallpox and intertribal warfare killed an estimated 20,000 New Zealand Maori.

In 1848–49, as many as 40,000 out of 150,000 Hawaiians are estimated to have died of measles, whooping cough and influenza. Measles killed more than 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population, in 1875, and in the early 19th century devastated the Great Andamanese population.[110] In Hokkaido, an epidemic of smallpox introduced by Japanese settlers is estimated to have killed 34% of the native Ainu population in 1845.

SOURCE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pandemic

DIABETES HISTORY

The condition known today as diabetes (diabetes mellitus) is thought to have been described in the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BC) Ayurvedic physicians (5th/6th century BC) first noted the sweet taste of diabetic urine, and called the condition madhumeha ("honey urine"). The term diabetes traces back to Demetrius of Apamea (1st century BC). For a long time, the condition was described and treated in traditional Chinese medicine as xiāo kě (wasting-thirst). Physicians of the medieval Islamic world, including Avicenna, have also written on diabetes. Early accounts often referred to diabetes as a disease of the kidneys. In 1674, Thomas Willis suggested that diabetes may be a disease of the blood. Johann Peter Frank is credited with distinguishing diabetes mellitus and diabetes insipidus in 1794.

In regard to diabetes mellitus, Joseph von Mering and Oskar Minkowski are commonly credited with the formal discovery (1889) of a role for the pancreas in causing the condition. In 1893, Édouard Laguesse suggested that the islet cells of the pancreas, described as "little heaps of cells" by Paul Langerhans in 1869, might play a regulatory role in digestion. These cells were named islets of Langerhans after the original discoverer. In the beginning of the 20th century, physicians hypothesized that the islets secrete a substance (named "insulin") that metabolises carbohydrates. The first to isolate the extract used, called insulin, was Nicolae Paulescu. In 1916, he succeeded in developing an aqueous pancreatic extract which, when injected into a diabetic dog, proved to have a normalizing effect on blood sugar levels. Then, while Paulescu served in army, during World War I, the discovery and purification of insulin for clinical use in 1921–1922 was achieved by a group of researchers in Toronto—Frederick Banting, John Macleod, Charles Best, and James Collip—paved the way for treatment. The patent for insulin was assigned to the University of Toronto in 1923 for a symbolic dollar to keep treatment accessible.

In regard to diabetes insipidus, treatment became available before the causes of the disease were clarified. The discovery of an antidiuretic substance extracted from the pituitary gland by researchers in Italy (A. Farini and B. Ceccaroni) and Germany (R. Von den Velden) in 1913 paved the way for treatment. By the 1920s, accumulated findings defined diabetes insipidus as a disorder of the pituitary. The main question now became whether the cause of diabetes insipidus lay in the pituitary gland or the hypothalamus, given their intimate connection. In 1954, Berta and Ernst Scharrer concluded that the hormones were produced by the nuclei of cells in the hypothalamus.

SOURCE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_diabetes

HYPERTENSION HISTORY

The modern history of hypertension begins with the understanding of the cardiovascular system based on the work of physician William Harvey (1578–1657), who described the circulation of blood in his book De motu cordis. The English clergyman Stephen Hales made the first published measurement of blood pressure in 1733. Descriptions of what would come to be called hypertension came from, among others, Thomas Young in 1808 and especially Richard Bright in 1836. Bright noted a link between cardiac hypertrophy and kidney disease, and subsequently kidney disease was often termed Bright's disease in this period. In 1850 George Johnson suggested that the thickened blood vessels seen in the kidney in Bright's disease might be an adaptation to elevated blood pressure. William Senhouse Kirkes in 1855 and Ludwig Traube in 1856 also proposed, based on pathological observations, that elevated pressure could account for the association between left ventricular hypertrophy to kidney damage in Bright's disease. Samuel Wilks observed that left ventricular hypertrophy and diseased arteries were not necessarily associated with diseased kidneys, implying that high blood pressure might occur in people with healthy kidneys; however, the first report of elevated blood pressure in a person without evidence of kidney disease was made by Frederick Akbar Mahomed in 1874 using a sphygmograph. The concept of hypertensive disease as a generalized circulatory disease was taken up by Sir Clifford Allbutt, who termed the condition "hyperpiesia". However, hypertension as a medical entity really came into being in 1896 with the invention of the cuff-based sphygmomanometer by Scipione Riva-Rocci in 1896, which allowed blood pressure to be measured in the clinic. In 1905, Nikolai Korotkoff improved the technique by describing the Korotkoff sounds that are heard when the artery is ausculted with a stethoscope while the sphygmomanometer cuff is deflated. Tracking serial blood pressure measurements was further enhanced when Donal Nunn invented an accurate fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer device in 1981.

The term essential hypertension ('Essentielle Hypertonie') was coined by Eberhard Frank in 1911 to describe elevated blood pressure for which no cause could be found. In 1928, the term malignant hypertension was coined by physicians from the Mayo Clinic to describe a syndrome of very high blood pressure, severe retinopathy and inadequate kidney function which usually resulted in death within a year from strokes, heart failure or kidney failure. A prominent individual with severe hypertension was Franklin D. Roosevelt. However, while the menace of severe or malignant hypertension was well recognised, the risks of more moderate elevations of blood pressure were uncertain and the benefits of treatment doubtful. Consequently, hypertension was often classified into "malignant" and "benign". In 1931, John Hay, Professor of Medicine at Liverpool University, wrote that "there is some truth in the saying that the greatest danger to a man with a high blood pressure lies in its discovery, because then some fool is certain to try and reduce it". This view was echoed in 1937 by US cardiologist Paul Dudley White, who suggested that "hypertension may be an important compensatory mechanism which should not be tampered with, even if we were certain that we could control it". Charles Friedberg's 1949 classic textbook "Diseases of the Heart", stated that "people with 'mild benign' hypertension ... [defined as blood pressures up to levels of 210/100 mm Hg] ... need not be treated". However, the tide of medical opinion was turning: it was increasingly recognised in the 1950s that "benign" hypertension was not harmless. Over the next decade increasing evidence accumulated from actuarial reports and longitudinal studies, such as the Framingham Heart Study, that "benign" hypertension increased death and cardiovascular disease, and that these risks increased in a graded manner with increasing blood pressure across the whole spectrum of population blood pressures. Subsequently, the National Institutes of Health also sponsored other population studies, which additionally showed that African Americans had a higher burden of hypertension and its complications.

SOURCE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_hypertension